Copernicus

Copernicus’ key arguments presented in On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543) are:

- The Earth is a sphere

- The Earth is made of earth and covered in part by a layer of waters

- The Earth is almost infinitely small compared to the size of the visible universe, as measured by the distance to the stars

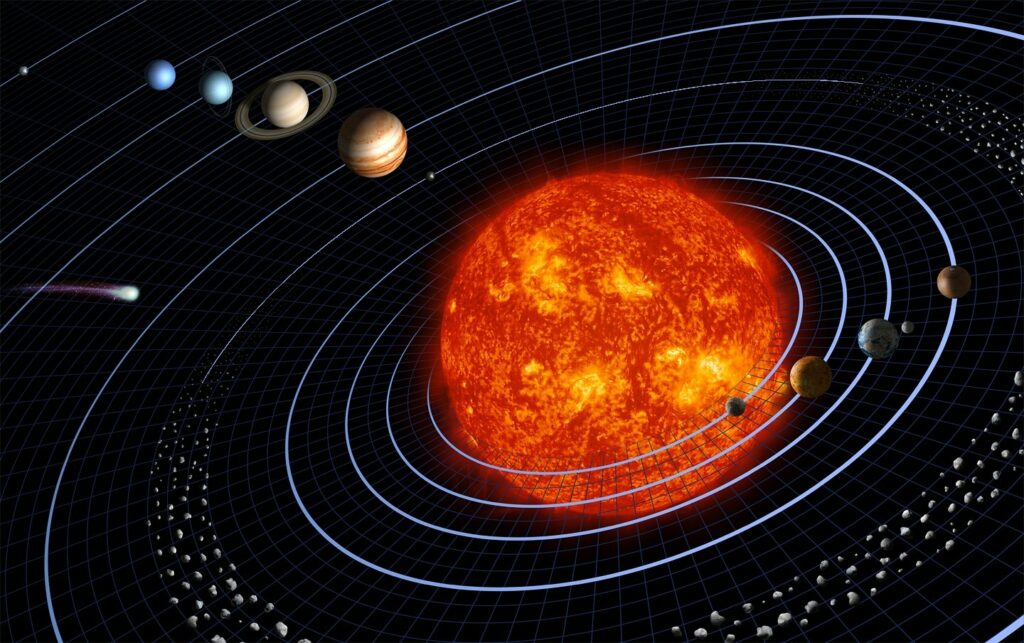

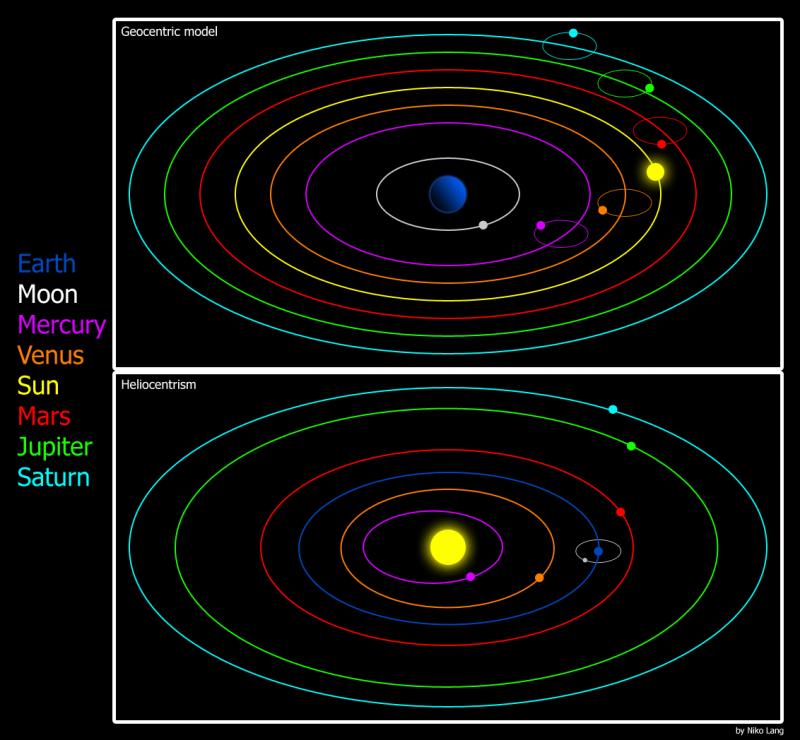

- The Earth is the third planet orbiting the Sun.

- All the other planets also orbit the Sun, not the Earth, with the exception of the Moon which orbits the Earth.

- The Earth moves. It follows three regular movements. It spins in a day. It orbits the Sun in a year. Its Northern Pole oscillates in several thousand years.

- It is possible that the Sun is a star like the other ones and the other stars be orbited by planets too.

Copernicus was prudent not to present his discoveries as such.

First, he reminded his readers that Aristotle already claimed that the Earth was round.

Second, he attributed to Aristarchus of Samos the opinion that the Sun was at the centre of the movements of the planets.

Third, he never published his work, which went in print only after his death. Copernicus only circulated sketches.

Above all, Copernicus avoided contrasting his presentation of the universe with that developed by his predecessors, especially Ptolemy and Aristotle. It would only have emphasized its radicality and unprecedented disregard for antic authorities.

This move was boldly made after him by followers like Galilee, who disregarded the Papal command that had been made to him to present both systems neutrally. Instead Galilee portrayed the proponents of a geo-centric universe like idiots.

However, Copernicus could not or would not shed all responsibility for his discoveries either. He did not attribute points 3, 6 and 7 to anyone else. As such, he still claimed credit for the boldest hypotheses he presented.

In retrospect, it is precisely Copernicus’ capacity to break free from tradition and to articulate a coherent presentation – coherent with itself and with all available observations – which impressed his contemporaries, adversaries and followers alike. To some of them he became an unparalleled source of inspiration and to others a unique source of annoyance.

In short, Copernicus was something entirely new in the eyes of his admirers and contemptors alike, to the point that they ended up coining a new word to allude to a radical breach with tradition, one that was directly inspired by his work: a revolution.

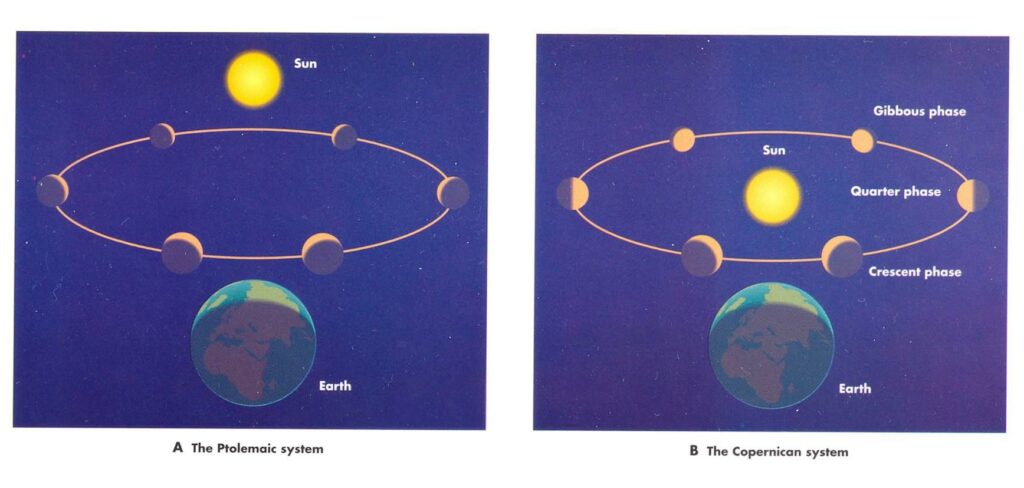

Indeed, over the course of the following century famous astronomers like Brahe, Kepler and Galilee made additional observations, which confirmed that Copernicus was right. Brahe and Kepler respectively measured and explained the movements of Mars, which became fully compatible with the Copernician views. Galilee observed the phases of Venus, the Mountains of the Moons and the Moons of Jupiter, which all became as many arguments in favour of a Copernician universe.

Last but least, through Galilee and Kepler, Copernicus became a major source of inspiration and tests for Newton and his theory of universal gravitation.

But Copernic also became a source of inspiration for political activists such as Giordano Bruno, who saw in a universe without center the ultimate justification for attacking the centralization of the Church operated by the Vatican and the Pope. Accused of heresy, condemned to death and burned at the stake, Bruno became a symbol for the revolutionary potent of Copernicus ideas.

Here we need to understand exactly why Copernicus work was revolutionary or, in Kuhn’s terms, a paradigm shift.

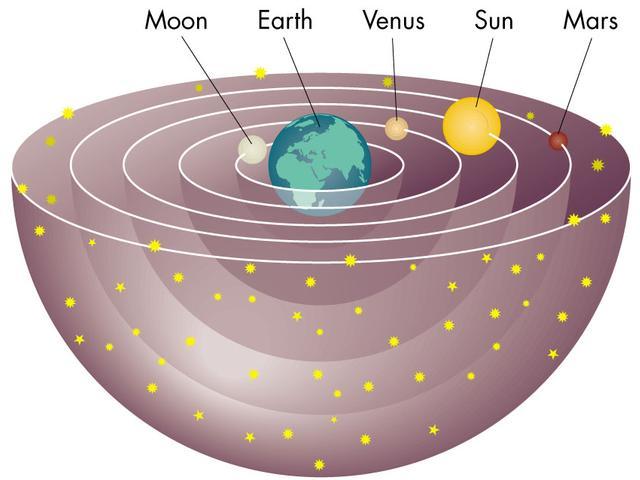

Before Copernicus, the dominant view was that the Earth was the center of the world and, essentially, the world itself. Planets, including the Moon and the Sun, and stars, were imagined to orbitate the Earth, which is what they do of course, and visibly so. They were also imagined to be radically different from the Earth itself.

The material world was imagined to consist of four elements: earth, water, air and fire. This distinction was largely identified with different layers: earth was mostly at the centre, water in a layer above earth, air in the layer above water and earth. The last layer was supposed to be made of fire, although no one had ever been there. Stars were imagined to be holes in a vault, from which the fire above the vault could be seen.

There remained some uncertainty about planets, those bodies which visibly moved between Earth and stars. Where exactly were they, and what was their substance? Aristotle (c. 340 BCE), probably like predecessors, proposed that they were embedded in spheres of crystal, which explained why they did not fall unto the earth and why it was possible to see through these spheres, up to the stars themselves. Aristotle admitted that the Earth itself was a sphere. Thus it seemed to be a sphere encased in other spheres, an elegant and harmonious explanation.

The whole explanation was ingenious. But it could be made better. Planets were strange. They moved across the skies were everything else, i.e. stars in almost infinite numbers, did not. Stars were at a fixed distance from each other, so that it was like the skies themselves moved, but the stars did not, whereas the planets were seemingly drifting slowing across the immobile stars. Planets were definitely anomalous. There were only seven of them compared with thousands of stars: the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Moreover, each planet seemingly had its own pattern of movement, which could not always be easily predicted. Each seemed to possess a will of its own. It is not surprizing that the ancients identified them with individual gods.

To a large extend Plotemy (c. 160 CE) seemed to fix that problem, by showing that it could be solved one considered that the planets did not only orbit the Earth but their own orbit at the same time (yes, it sound complex, and it is). By allowing for the movements of each planet, this change destroyed the beautiful hypothesis of the crystal spheres. But for fourteen centuries no one proposed any better explanation.

Copernicus learned about these theories during his studies in Northern Italy.

Copernicus chose to blast the antic views about the universe. He did not claim it. Instead, he opted for opening his demonstration by definitive arguments.

First of all, he explained that the Earth is spherical. To be certain, this was nothing new, and for good measure he quoted Aristotle’s arguments alongside his own. However, by reminding his readers about the rotundity of the Earth, Copernicus made certain to induce the idea that this made the Earth no different from the Sun or the Moon. Thus, he immediately did away with the idea that the skies were necessarily of a different nature than the Earth. It was only the beginning.

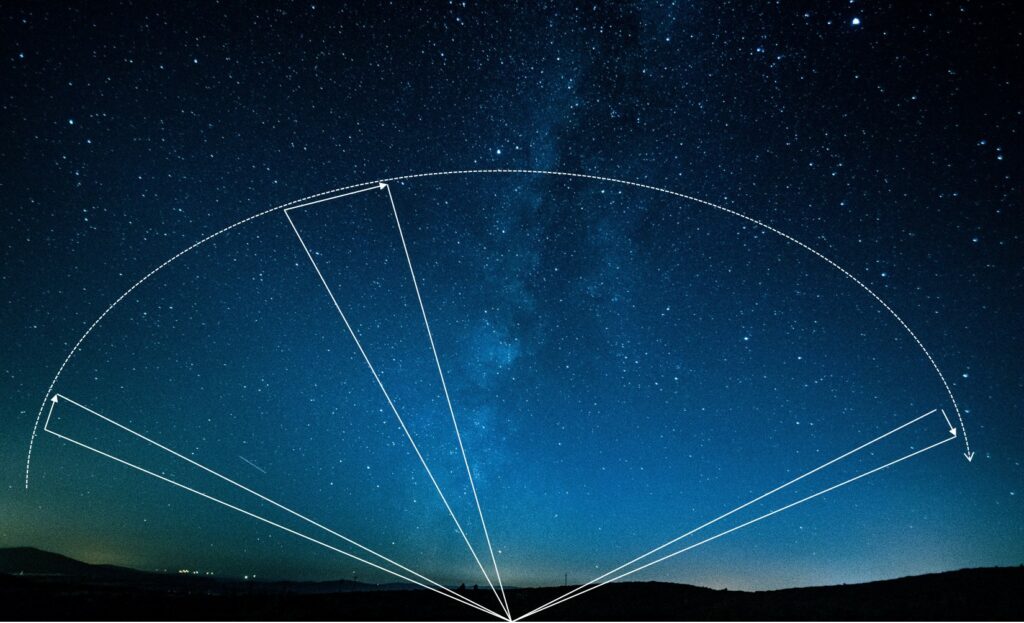

Second, he did away with the idea that the Earth was the universe, and that the skies were only the outer peripheries of that world. He used a very simple, inescapable mean: geometry. He noticed that if the Earth was really massive compared to the skies, which was logical if the skies were merely thin spheres orbiting the Earth, then this should be visible from the Earth. Two stars on a comparatively close sky would appear closer from one another when low on the horizon, either rising from it or descending towards it, than when high in the sky. The arc between them would appear smaller when low on the horizon than when high. Only stars at an almost infinite distance from the Earth would always appear at the same distance from one another while (apparently) traveling through the night sky. This, however, is what can be observed. This simple observation: the distance between the stars is always the same (it is actually to the naked eye only, but Copernicus did not possess a telescope for they had not been invented yet) is proof that the size of the visible universe is almost infinite compared to the Earth. Conversely, the Earth is a mere point in the universe, like planets and stars.

With these two simple arguments, and without ever claiming it, Copernicus had completely destroyed the traditional view of the universe and replaced it with a new one. His choice of construction shows that he was conscious of the necessity to completely rebuilt the conception of the universe to propose a coherent one. He certainly was aware of the paradigm shift or the scientific revolution, although he possessed neither words to express the global change he was introducing.

In many ways, although Copernicus acts like the first revolutionary scientist, he stuck to the formalities of tradition by (apparently) upholding ancient conceptions and never claiming to distance himself from them. This further indicates how uneasy he was with his move. After all, Copernicus was a shrewd administrator and a clever political mind. He calculated just how far he could safely go.

Thus, he would next place his demonstration that the Sun is the unique center of all planetary movements (except the Earth) in the continuity of Aristarchus of Samos, an astronomer about whom we know nothing except that he would have entertained similar views. In any case, Aristarchus cannot have been a source of inspiration. How Copernicus came to his conclusions except by the sheer power of deduction is impossible to know.

Illustrations :

Nicolaus Copernicus, The “Toruń Portrait” by an anonymous painter, c. 1580, probably after a lost self-portrait

Learn more :

A presentation of the Copernican system in Wikipedia

Nicolaus Copernicus life and work in Wikipedia

On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres in English.

Watch a discussion of the Copernican system :