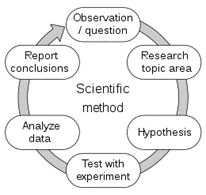

The scientific method

There is a scientific method that answers the scientific ideal. It is both more simple (in theory) and demanding (in practice) than usually assumed.

Coherence and facts are the bases of solid explanations.

1. Coherence and observable facts (definitely)

The scientific dream is the discovery of the law of the universe. This law goes by under various names. It is sometimes dubbed the “equation of god”, or “theory of everything”.

As a consequence, a scientific work should propose a coherent and factual explanation. It should be coherent, not contradicting itself, its different elements confirming each other. And it must apply to facts that can be observed and confirmed, in other words verified, by independent observations. These criteria are also referred to as internal and external coherence. They ensure that scientific works contribute to fulfilling the scientific ideal.

To better understand how this applies to concrete explanations, let us take an example. The explanation that God created the universe is coherent internally, but not externally. Humans certainly understand that as the almighty being, God can create the universe. But God is not a fact that can be observed and confirmed by human observations. He does not need it either. Regarding God, humans need to believe. They cannot verify or judge. As such, a unique, global divine creation falls beyond the realm of science, although one may consider that a coherent, unifying theory indirectly confirms the explanation, since a unique creation would imply a universe obeying laws and explainable by a unique, general theory. In that respect, faith and research do not contradict themselves.

2. Simplicity and elegance (preferably)

Another consequence for the scientific ideal is the search of simplicity and elegance. This other criterion is often known as “Occam’s razor“, after one of the earliest authors to have expressed it. It means that unnecessarily complicated developments are not to be retained in scientific works.

3. Publication (best practice, not method)

Internal and external coherence are fundamental criteria to assess scientific quality. Peer review is not in itself a criterion of sound scientific production. It is a best practice that must be strongly encouraged, just like publication, constructive criticism, interdisciplinarity or open science. However, such best practice are neither necessary to distinguish sound scientific works, nor always possible. The same applies to mathematization. The transcription into symbolic language is not per se a sign of scientific quality. It can be a powerful way to simplify key explanations, but is not necessarily and can also be used to make a work more obscure.

4. Observations or experiments

There is a marked tendency in some academic fields and publications to valorize experiments, observations that result from circumstances that have been to a large extend created for the purpose of observation. There is no hierarchy between experiments and observations. The same difficulties in replicating and generalizing results can be observed in both cases.

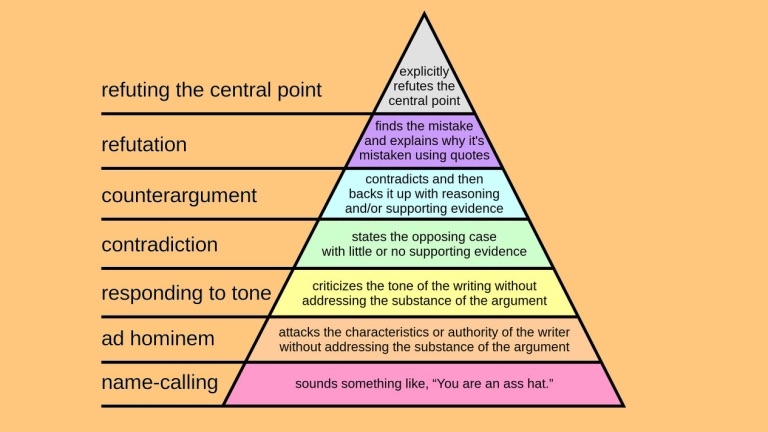

5. Ad hominem (certainly not)

A scientific work must be accepted or rejected on its own merits alone, not on the name of its author. The argument ad hominem, and its variants, should be proscribed. Humans being humans, approaching such a goal obviously requires a very strong governance. Academic life, the regulation of scientific production, is therefore, in practice, a necessary component of scientific life, with its advantages, and limits. It is obvious that some people with an interest in science must feel excluded from restricted academic communities and therefore be driven to condemn academically-correct science per se, while others, who feel they belong to the community, might prove themselves insufficiently critic with the production of their peers.

It is impossible to completely stamp out these twin evils, as anyone who observes exchanges about flat-earthing and climate change denialism can attest.

However, one can at least avoid the excesses of arguments ad hominem, including and perhaps especially when they are not nakedly used but when they are masked by (big) name-dropping. In that respect, recent use of the work of Popper and Kuhn deserve particular scrutiny.

GO FURTHER